Is Gain Like A Balloon? |

August 11th, 2014 |

| experiments, music, sound, tech |

It may help to imagine inflating a balloon around the mic as you increase the gain, since the input gain also affects how large an area around the mic will pick up sound. This is important in managing feedback, as well as in getting a realistic sound out of the instruments. -- All Mixed UpThis model is clearly right to an extent, because the farther something is from the mic the more you have to turn the gain up in order to hear it. If you compare micing an instrument at 2" to micing it at 20", you'll have to turn the gain up more at 20" to get the same level but you'll also pick up more different sounds. Instead of a tiny balloon picking up only the way the instrument sounds at the particular point you miced, you have a big balloon that is somewhat closer to how we normally hear the instrument by combining sound from lots of areas. [1]

Sometimes, however, people take the balloon model a little farther. A larger balloon starts enclosing more points, so people think turning up the gain increases what instruments will get included at all. Specifically, some people think that if you're on a standard mixer and your initial gain is set high but your faders are low, that this gives you more potential for feedback than if you set both your gain and faders to an intermediate position. How? The idea is that because that initial gain is set higher then the balloon around the mic is larger, which means you're pulling in more stage noise from things like monitors.

I was talking to a friend with this mental model, while I had the model that each gain is just a volume knob. In my model it doesn't matter whether you set the gain high and the fader low, or the gain low and the fader high, you'll still get the same output. Well, if your gain is too high you'll overload it and get distortion, and if it's too low you'll get noise from inside the mixer, but the amount of stage noise you get will be constant. In my model you can't fix stage noise problems like feedback by adjusting your gain staging; you have to turn something down or change how things are positioned on stage.

We were both pretty confident in our mental models. I couldn't figure out how the mixer's preamp would be controlling the balance of signals coming into the mic, while they trusted what they had read and experienced. This was an empirical question, though, so we decided on an experiment:

- Set up two things making sound at different distances from a microphone.

- Turn up the gain and down the fader keeping the overall output level constant.

- Do the relative levels of the two sound sources change?

If my friend was right, the higher we put the gain then the more we would hear of the farther sound source. If I was right then we would hear them in the same ratio however we set the gain.

I set things up:

The two cell phones were set to make sine waves, the close one at 440Hz, the farther one at 907Hz. These numbers were chosen arbitrarily, but the goal was to have things that were clearly distinguishable. They were set up as close to on-axis to the mic as I could manage, with the 440Hz tone at about 1" and the 907Hz at about 6". The mic was an sm57, connected to a Spirit Folio mixer. For recording, the output of the mixer was connected to the input of an 1818 VSL audio interface, and from there to a laptop running Audacity. I started it in one gain configuration, ran it for a bit, leaned over and said "start" into the mic, and then adjusted one knob up and the other down to switch to the other. I watched the recording input level on the computer to try and keep the same total volume. When I had finished adjusting I said "stop" and recorded a little longer. Here's what it sounded like, first in one gain configuration and then the other: frequency-experiment.wav. You want to compare the very start to the very end.

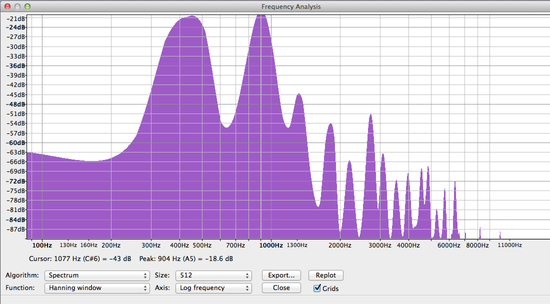

I couldn't hear a difference, but maybe we could tell them apart with an FFT by comparing the relative heights of the peaks? Here's case A:

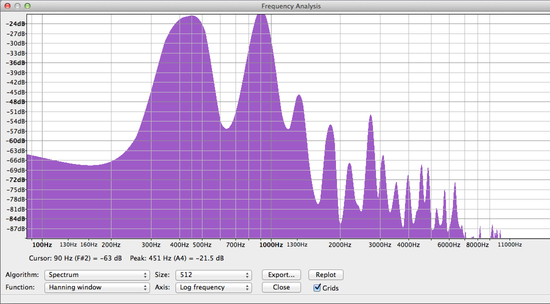

This has the first peak at 451Hz (-20.5dB) and the second one at 904Hz (-18.6dB). And here's case B:

This has the first peak at 451Hz (-21.5dB) and the second one at 904Hz (-19.6dB). So aside from being 1dB lower in case B, probably because I had slightly less combined gain in that case, the ratios seem identical. [2]

It looks like we should demote the balloon model down to "rough tool for thinking about things" and instead go with the "chained volume control" model. Which also means, sadly, that we can't fix stage noise issues by improving gain staging.

(Are you wondering which case was which? Pnfr n jnf tnva-uvtu-snqre-ybj naq pnfr o jnf gur bccbfvgr.)

[1] The downside is that if there are multiple sources of sound, like

multiple instruments, monitors, or crowd noise, then if you mic at a

larger distance you start getting more of that mixed in with your

instrument. Which you generally don't want.

[2] It's weird that 440Hz came out as 451Hz and 907 as 904. I wonder whether this was some kind of interference or bad synthesis?

Update 2014-08-14: Just a limitation of FFT and the number of buckets.

Comment via: google plus, facebook, substack